Developing themes is the next phase I’m now moving into. Re-reading Chapter 4 of this book. Summarising here in a thread as I go. 1/

Developing the themes in reflexive thematic analysis involves a constant back and forth of zooming in and zooming out. You must also give yourself enough time to do it… “It’ll probably take at least twice as long as you expect”. 2/

What is a theme? “A theme captures a pattern of meaning across the dataset”. In reflexive TA a theme represents a shared idea, and is different to a topic summary. 3/

“A topic summary is a summary of everything the participants said about a particular topic… they unite around a topic rather than a shared meaning or idea.

A theme in reflexive TA is organised around a central concept. It is not simply a description or regurgitation of what the data says, but rather a synthesis of that data by the researcher.

Generating themes is an active, creative process. @ginnybraun and @drvicclarke invoke the metaphor of the researcher as a sculptor and the data as the marble or wood that the sculptor is working on.

It’s easy to get lost in this phase of reflexive TA. It’s all part of the process. In some ways you just need to accept it. But it can also be playful and creative. Let’s hope I can find this flow state.

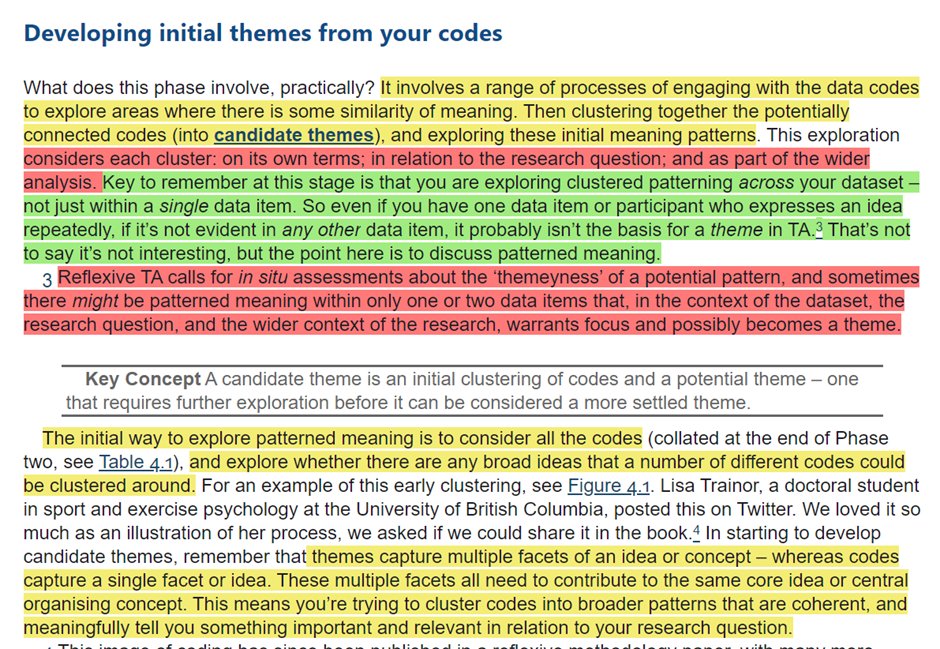

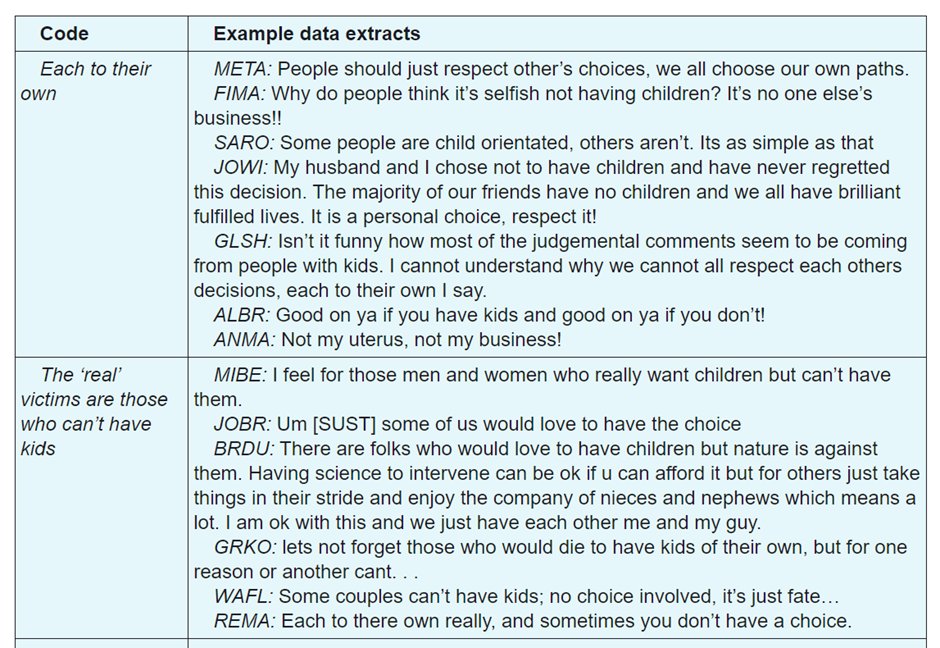

We start by finding similarity of meaning in the codes and clustering into candidate themes. To be a theme in reflexive TA, the pattern likely needs to be seen across the data rather than from a single data source (but like all things Big Q, there is flexibility).

Once all the coding is done, zoom out and look for any broad ideas that can be clustered together. Codes are the multiple facets that form a theme and contribute to the central idea summarised in the theme.

9/

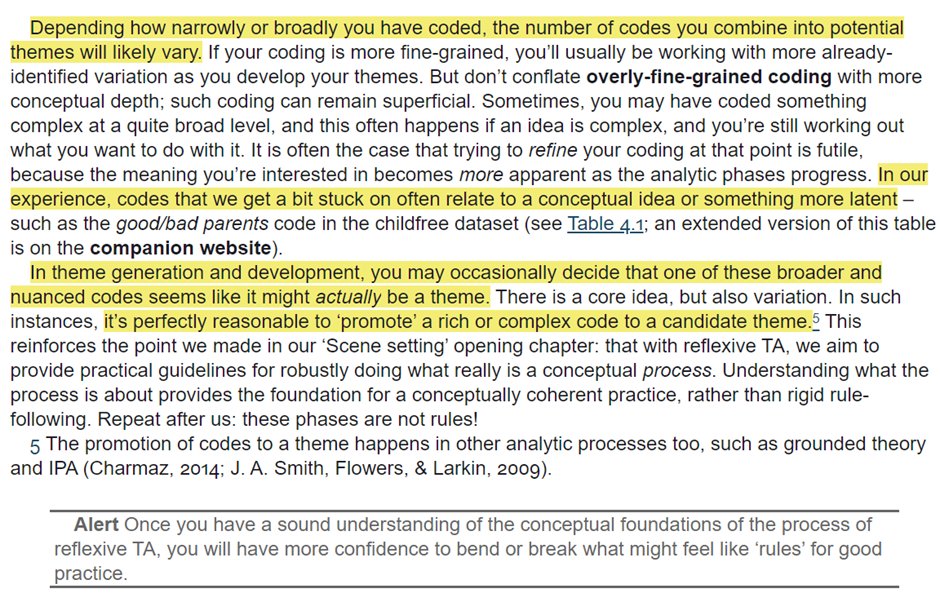

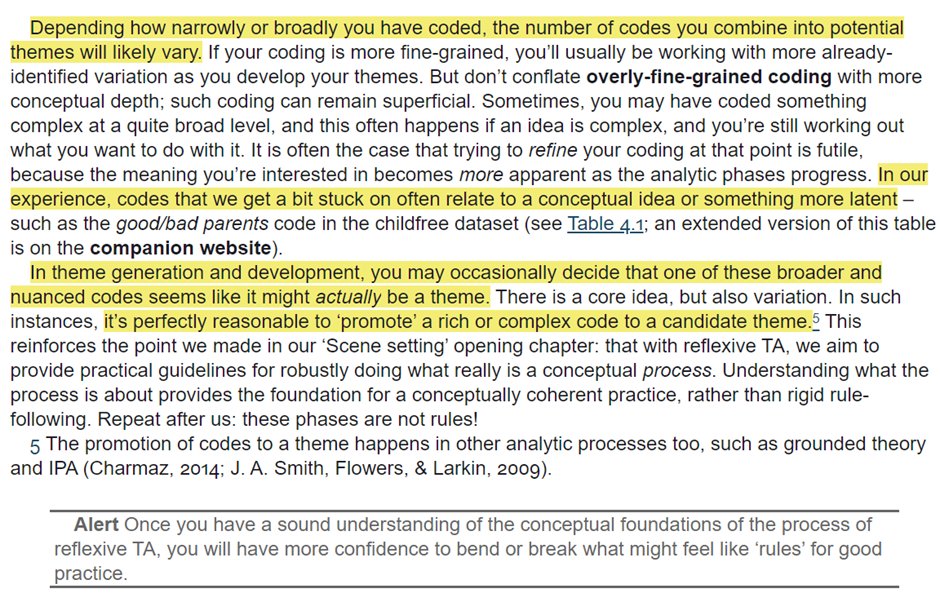

Fine-gained codes are not a guarantee of quality and can be used to generate superficial themes. We need to aim for depth of meaning generated by and within the theme. Codes themselves can become themes too.

Reflecting on these examples, all these codes have multiple sources. Many of the codes I generated inductively only have a single source, perhaps suggesting I have was coding very finely. Certainly towards the end, I was coding more broadly.

I will ponder this during the theme generation. I am sure that some of the codes will be aggregated together because many have similar ideas and it’s just the syntax of the code which is different.

12/

This initial phase of theme generation is like a scouting mission. Everything should be held very lightly and you should be prepared to let go of it and go with something else. “Consider the story they allow you to tell about your dataset”.

Ask youself three questions according to the authors:

1/Does it capture something meaningful?

2/Is it coherent/consistent with the idea and the data?

3/Is it clearly bounded? (I guess this means make sure it’s not nebulous or ambiguous.)

14/

You might like to use maps to plot out the themes. It might help to think about the provisional themes, the link between the themes and the story your themes tell.

The primary focus of reflexive thematic analysis is at the theme level (zoomed out) although subthemes can be used judiciously. If I read this correctly, you should try to stay zoomed out generally.

Three layers in reflexive thematic analysis

1/Overarching themes

2/Themes

3/Subthemes

17/

Generally reflexive thematic analysis does not make use of overarching themes. But they’re there if you choose to use them.

Themes is where the main bulk of the work happens with reflexive thematic analysis.

Note to self:Watch out. Subthemes add structural complexity, but this may come at the detriment of the analytic depth of the theme itself. Reviewers may even request it but @ginnybraun and @drvicclarke say “resist!”

Mapping is a tool that you should use to help you develop your analysis.

Five things to remember during theme development…

22/

1/ Your themes don’t have to be all encompassing. It doesn’t represent everything. Rather you need to use them to retell the story that that data is telling you.

2/ Each candidate (and final) theme must be organised around a central concept.

3/ Each theme should be held lightly. Be prepared to toss it out.

4/ You can start with lots of candidate themes, but in the authors’ experience, the “right” number is 2-6 themes for a 8000 word paper.

5/ Avoid a question/answer type approach to developing themes as this may lead you to generate superficial themes. Do however, keep the research question at the back of your mind.

My summary of box 4.2: Spend time developing deep &nuanced themes and avoid superficiality which might be signalled by too many themes.

There are different ways of writing up. You may use a paper to report on a single overaching theme with 2-3 themes.

Time management can be an issue here. Don’t spend too long on the initial theme development as some of the themes may not make the final cut.

Remember that reflexive TA is recursive (so you can come back to it later), and that no analysis is perfect (you just have to trust in the process).

After you’ve worked to generate provisional themes in phase 3, phase 4 zooms back in to check the themes against the data. There’s a lot of zooming in and out, and going back and forth between phase 3 and 4.

Phase 4 is partly a quality control exercise (validity check), but it’s also a quality improvement exercise (developing richness of the themes).

32/

Theme viability.

Is the theme true to the data? And does the theme have a core point describing nuance and diversity in the data that addresses the research question? Is there a clear central idea or organising concept?

Other aspects.

Is it clearly delineated?

Is there enough data to support the premise?

Is the data coherent enough?

Does the theme tell me something important about the data in response to the research question?

A reminder to hold those provisional themes lightly. Be prepared to go back to the drawing board, or to use the eraser and revisit ideas. “Am I trying to massage the data into a pattern that isn’t there? What am I not noticing here?” etc.

@ginnybraun and @drvicclarke emphasise robustness AND flexibility. This sort of reminds me of the metaphor of jazz improv. There are certain musical rules that jazz musicians follow, but they develop an awareness of when those rules can be broken to create a unique piece.

This in turn reminds me of some of Donald Schon’s observations in Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. First Edition. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass, 1987. .

37/

Educating the reflective practitioner : Schön, Donald A. (Donald Alan), 1930- : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet ArchiveBibliography: p345-348. – Includes indexhttps://archive.org/details/educatingreflect00sch

From memory Schon observed architecture apprentices and musicians, and noted how the experts “taught” the learners to do the basics before allowing them to vary. Anyway, I think I’ve veered off topic here.

38/

The themes should be reviewed in context with the data to ensure that you’re being faithful to your interpretation of the data.

This was an interesting observation. Each time we look at the data with a different question, the data changes subtly because we interpret it differently.

It’s not about the frequency that an idea appears in the data. It’s about your interpretation of an idea that goes towards answering the research question you’re asking. Common patterns are often irrelevant or don’t contribute to understanding.

Mapping in this phase is useful. Mapping reminds me of story boards that filmmakers use to plan their films (you can see them at the end of each #Mandalorian episode). This also reminds me that there is an element of creativity in Big Q research.

Reminder – a topic summary is not a theme! A theme has a central organising concept with a pattern. Topic summaries are like containers for codes without any sense-making or pattern being established.

Contradictions can be handled a few ways. Generally a theme should be aligned with the data that’s contained within it. You can’t have a theme saying X but then have the data saying X’ (X’s complement – I’m using set notation for Venn diagrams here)

Themes can contain contradictory data, but just not contradict the theme itself. And the theme can actually be ABOUT the contradiction in which case the contradictory data actually illustrates and supports the theme.

Phase 5 is about defining and naming the theme.

I remember when I did my lit review my definition according to what the authors wrote wasn’t quite what my supervisors were expecting.😅

Four questions to incorporate into the def’n.

Central idea

Boundary

Uniqueness

How it contributes to the analysis.

Naming the theme is important and it can be fun. It is important because this is how the audience will initially interact with the thematic analysis. So aim to leave an accurate and memorably impression on the reader/listener. The name must tell a story too.

The idea that the name must tell a story is interesting in itself. Our own names tell us about ourselves. They can give away our ethnicity, can tell us who are fathers were, can tell us about what our parents believed, what aspirations they held for us. Names are important.

49/

Naming things can be fun. Again, it can be an act of creativity.

And that’s the end of the chapter.